Stories from the Archive 1: The Fight for Sheffield's Green Belt

The fight to create and keep the Green Belt around Sheffield has been going on for nearly one hundred years.

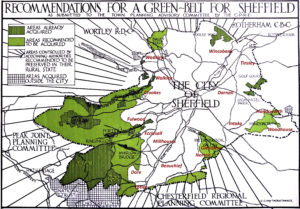

In 1937 the CPRE surveyed land around Sheffield and submitted their plan for a Green Belt. In 1938 their proposal was accepted by Sheffield City Council. In the north, south, east and west – farms, woods and moorland were ear-marked for the Sheffield Green Belt.

Courtesy of The Totley History Group. Copy also held at CPRE Archive Ref: CPRE/A421.

In the 1930s people could go by bus into the Peak District or escape the smoky city by walking from town to green spaces. In the 2020 COVID lockdown many people discovered, perhaps for the first time, that having a Green Belt meant they could get out of the house for some exercise and enjoy walking on the moors, along our river valleys and through woods. But it could have been so different. Throughout its history, CPRE has campaigned against the development of houses, factories and opencast mines in unsuitable places in the Green Belt. Thanks to their efforts we can still enjoy the many areas around our city that they protected.

How did it start?

In 1927 the Duke of Rutland sold Blacka Moor to a developer. To save this special place from development Alderman J.G.Graves bought it, and in 1933 gifted it to the people of Sheffield. Then in 1935 a builder bought the land between Whirlow Bridge and Dore Moor Inn to build 900 houses.

Ethel Gallimore (as she was then) told the Sheffield City Planning Committee of her idea to keep this area as a green ‘Gateway to Derbyshire’. She lobbied the Council to buy the land from the developer. It also bought the Burbage and Houndkirk Moors for a water catchment area. By 1936 it owned much of the land to the west.

Ethel directly approached the Graves Trust and T Walter Hall to buy further threatened land which they then gave to the city. Thanks to their generosity areas such as the Porter, Mayfield, Rivelin and Limb Valleys and Ryecroft Glen were protected.

It was the start of the effort to secure a Green Belt for the city.

The Sheffield Council showed much foresight and bought agricultural land, farms, woodland and moorland for the Green Belt. They even bought land south of Norton outside the city boundary so that the Green Belt in the east would link together with the Green Belt in the west.

By the end 1945 nearly all the land in the proposed Green Belt Plan of 1938 had been secured. It’s hard to think of it now but it was seen as important to have farms close by to provide fresh milk and food for the people who lived in the city.

What came next?

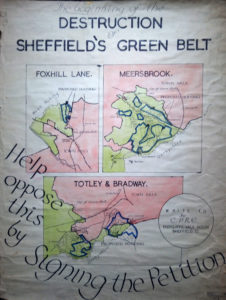

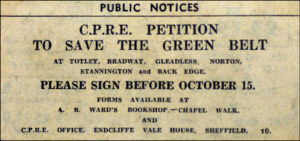

After the war there was an effort to clear Sheffield’s slums and build new houses. The National Coal Board wanted to have an opencast coal mine near the Edward VII hospital, a steel works wanted to build in the Loxley Valley and sites were needed for refuse tips. The fight was on to stop all these threats to the Green Belt. The CPRE became involved in many campaigns and the hard work began to keep it all safe.

Ethel had married Gerald Haythornthwaite in 1937 and together they were the leading lights of the CPRE. They worked tirelessly to keep the Green Belt. The first campaign after the war was in 1946 where they successfully stopped house building on the moors above Totley. Totley was to feature in further CPRE campaigns.

Greenhill, Bradway and Mosborough

In 1950, a public inquiry into a plan to build an estate at Greenhill and Bradway, failed to get approval. The Minister for Housing refused permission as it would be right next to the Derbyshire Green Belt without a gap. Sheffield said it would run out of land to build houses in two years’ time which made Derbyshire worried that Sheffield had its eye on Dronfield!

In the end a housing estate was planned for Mosborough, then in Derbyshire, which wasn’t in a green belt. In 1962 the Boundary Commission announced changes to Sheffield’s boundary that would include Mosborough. The Sheffield CPRE and Derbyshire CPRE had a joint campaign in 1982 because the Moss Valley had been left out of the Green Belt and the people of Killamarsh demonstrated outside the House of Commons because their valley had been left out too.

Rivelin and Stannington

The public inquiry in 1964 into planning applications for housing in the Rivelin Valley and at Stannington was a major event. CPRE encouraged people to attend and object. They even issued a leaflet that told people which buses to catch to Stannington from town and many people raised their objections. The application to build was opposed by West Riding County Council and CPRE. Gerald put the case against with a 22-page statement. Even a 15-year-old schoolgirl from Stannington spoke against the plan.

Green Belt land was saved in the Rivelin Valley, but the Minister of Housing ruled in favour of building at Stannington.

Loxley Valley

So many people turned up to the Loxley Valley public inquiry in 1975 at the Town Hall that it had to be moved from a conference room to the council chamber. The planning application was for a factory and housing. Sheffield Council had already turned it down and CPRE also objected. In the end the government minister ruled that the houses could not be built. However, the factory got planning permission but with certain conditions.

Whirlow Hall Farm and Oakes Park

Throughout the years there were many campaigns – some were for small pockets of green belt others more substantial. Some places, such as Ryecroft Farm, came under threat time after time. There was continual battle to save Whirlow Hall Farm and a campaign against building a 150-million-pound leisure complex on the historic Oakes Park at Norton. Today both places continue to serve a useful purpose for our community.

The Green Belt today

Well, it gets nibbled away at! But CPRE and the Friends of Loxley Valley have just been successful in the most recent campaign to stop a housing estate development there. In the past town planners thought it was just about stopping cities spreading out or providing the ‘lungs of the city’. Today we know that it is also about preserving the landscape for nature and helping us all with our health and well-being.

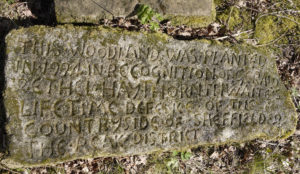

In remembrance of their work

Just opposite Dore Moor Inn, at a place saved by the 1936 Whirlow Bridge to Dore Moor campaign, there stands a small wood, known as Haythornthwaite Wood. It was planted by CPRE – with help from Gerald himself! – and dedicated to Ethel and Gerald in honour of their lifetimes’ work.

And what of the future?

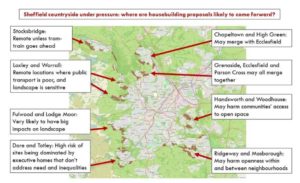

Sheffield is required to build 55,000 new houses by 2039 and CPRE is campaigning to protect Sheffield’s Green Belt. Up to 11,000 of those new homes could be built in the Sheffield Green Belt, affecting communities all around the city, from Burncross to Stannington, Fulwood to Dore and Norton to Beighton.

If we want to continue to enjoy the countryside on our doorstep, we all need to support the CPRE’s Green Belt campaign. They want future developments to be on brown field sites in Sheffield. That way we can enjoy our green spaces and have a city designed so that it works for all of us. We haven’t lost the Green Belt yet, but the work of Ethel and Gerald Haythornthwaite still goes on at CPRE.