Stories from the Archive 4: Digging In Against Quarries

One of the Sheffield Branch of the CPRE’s longest-running campaigns is against the destructive impact of large and intrusive quarries and opencast mines. Eldon Hill Quarry is an example of campaign success.

Delving into Quarries

Opencast mines in South Yorkshire and North East Derbyshire, and large limestone quarries in the Peak District have been big issues for the Sheffield Branch of the CPRE. It has campaigned against any mine or quarry that would damage the beauty and tranquillity of rural landscapes. While the CPRE has tried to protect natural beauty, they have also argued against quarries because of noise, dust, traffic and, more recently, climate change.

The branch has used a range of co-ordinated campaign techniques, from writing policy articles and lobbying local and national government to influence local planning and national legislation, to leading campaigns against specific planning applications. The CPRE has written letters of objection, called for public enquiries and encouraged members and other organisations to object. At different times, they have mobilised national institutions, community groups, Lords and MPs, as well as ordinary individuals.

Opencast

Deep and opencast coal mines have left their mark on South Yorkshire’s landscape, alongside sand, gravel and limestone quarries. Large-scale peat removal used to take place on the lowland peat bogs of Thorne and Hatfield Moors, but the main permissions have now been revoked. Recently, there have been applications to extend limestone quarries in Doncaster and Rotherham, while there may be renewed pressure to find new opencast coal sites. At different times in the past, the CPRE has preferred coal imports and nuclear to local opencast coal. Now, the CPRE campaigns against coal-fuelled power stations because of the fossil fuel’s impact on climate change.

Limestone Quarries

Limestone quarries have been one of the CPRE’s major campaigns in the Peak District since the 1920s. The region is a major source of limestone, mostly for aggregates, with many extensive and ill-defined quarry permissions awarded before the National Park was established in 1951.

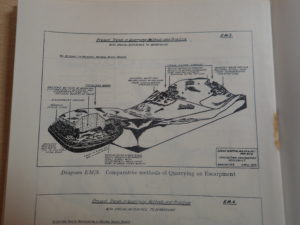

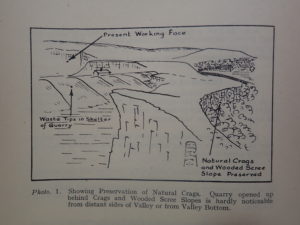

As part of the Join Committee for the Peak District National Park, the CPRE commissioned an engineering geologist to report on quarrying in the Peak District. The 1950 report included examples and diagrams of good quarries, which did not impact the landscape, and bad quarries, which did. The report recommend that existing quarries should continue to develop, however these and new proposals should be controlled by the planning system.

Eldon Hill

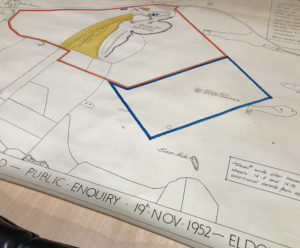

In 1968, a quarry company applied to the Peak Park Joint Planning Board, now the Peak District National Park Authority, for permission to extend Eldon Hill Quarry and join it with Sparrowpit Quarry. The CPRE leapt into action as soon as they saw the Eldon Hill application, because the company wanted to completely remove the top of the hill. The response was a textbook example of their campaign strategy.

The Quarry

Eldon Hill is a limestone hill in the northern Peak District, between the villages of Castleton and Peak Forest. Permission to quarry was granted in 1950 after an unsuccessful CPRE campaign and a public enquiry. Since then, much of the hill’s northern and north-western slopes have been removed to provide a vast amount of road-building limestone. In 1995, a member of the House of Lords called the quarry the best-known eyesore in the Peak District.

The Planning Application

The quarry company was Thomas W. Ward of Sheffield, which had been founded by Ethel Haythornthwaite’s father. It applied to quarry a one-acre wedge of land to join Eldon Hill with Sparrowpit quarries. This would have removed the crest of the hill and changed the skyline forever.

The Campaign

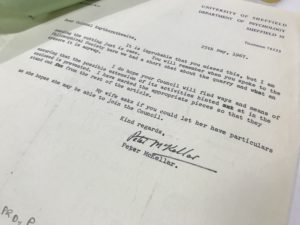

It all began on 25th May 1967 when Sheffield resident Peter McKellar sent Gerald Haythornthwaite a news cutting to alert the CPRE to the planning application. He had been inspired to write after attending one of Gerald’s talks about quarries. The news report mentioned how potholers wanted to buy the land to prevent the extension and save important underground mine remains.

The CPRE’s campaign focused on three aspects.

- Removing the summit would spoil the landscape.

- Installing large quarry machinery would increase dust, noise and road traffic.

- A government statement issued during a previous quarry extension in 1953, that any further quarrying should be limited.

The CPRE did not mention the underground mines or a nearby scheduled monument of a prehistoric burial mound. At this time, the CPRE was focused on natural beauty and tranquillity. Today, the protection of scheduled monuments and listed buildings is an important factor when objecting to development. The lead mine’s importance gained statutory protection when it was scheduled in 1985.

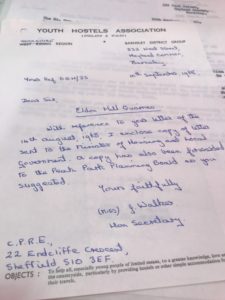

In 1968, the CPRE deployed an effective campaign strategy that they had used before. They began by writing to the Planning Board to register their objection and asking for an acknowledgement that it had been received. Then, they asked other organisations and CPRE members to object. They sent out a typed template letter that laid out what to object about and to call for a public enquiry if permission was refused and Ward appealed against the decision. The enquiry was an opportunity to present the case against the quarry and demonstrate public opposition. Objections were to be sent to the Planning Board and the Minister of Housing and Local Government. The template was accompanied by the CPRE’s own letter to the Minister and a request for objectors to copy their letters to the CPRE.

The campaign lasted for three months during 1968. It mobilised a wide range of organisations, from the national to the regional to the very local. Objections came in from the Countryside Commission, National Trust, National Parks Commission, YHA, Ramblers Association, Holiday Fellowship, Peak District Mines Historical Society, Chesterfield Town Council, and Ireton Wood and Idridgehay WI (near Wirksworth).

Peter Jackson, MP for the High Peak between 1966 and 1970, and the Rt. Hon. Lord Molson of Kelso also objected. Lord Molson was an influential opponent of the quarry. He wrote to the Minister and stated how Harold MacMillan had ‘deliberately restricted the permission he gave in 1953 with the intention of preserving the outline of the summit of Eldon Hill. I submit that there is no justification for extended planning permission.’

Gerald was conscientious in replying to letters from organisations and individuals, and promised to keep everyone informed of progress. There are 30 pieces of correspondence with organisations and individuals in the archive from August 1968 alone.

The Result

In 1968 the Planning Board refused planning permission. The planners felt that the ‘conspicuously sited quarry has already done serious damage… it would be wrong to allow any extension of working, however small, beyond the limits laid down in 1953.’ This was reported in regional press.

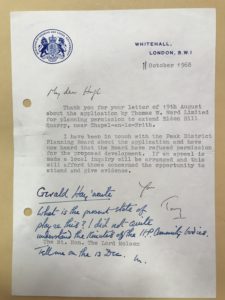

The Minister replied to Lord Molson on first name terms – as Hugh – on the 11th October 1968 to confirm that the Planning Board had refused permission and that any appeal would result in a public enquiry. Lord Molson passed this letter to the CPRE, where Gerald annotated it with a note to keep an eye on developments and keep the campaign active.

Ward applied again to extend Eldon Hill Quarry in the 1980s. This time, they appealed on refusal and a public enquiry was held in Buxton. The CPRE presented their case against and, in 1985, the appeal was dismissed. New owners, RMC Aggregates, applied once again to extend the quarry in 1995. This was the year Eldon Hill was mentioned in Parliament as an example of why ill-defined and extensive mineral permissions granted between 1948 and 1981 needed revising. The CPRE once again objected and the application was refused. The quarry closed in 1999 and now stands unused with vegetation starting to grow on the quarry face.

Today

Quarries and opencast mines in Derbyshire and South Yorkshire are still a major campaign issue for the CPRE. Old mineral permissions are no longer a threat to unrestricted quarrying in the Peak District thanks to CPRE lobbying. The National Park Authority served prohibition orders on these quarries, and national legislation has brought them under modern planning controls. The CPRE oppose open cast coal mining because of the impact it has on the landscape and the need to switch away from dirty fuels like coal to avert the worst impacts of climate change.