Stories from the Archive 5: Shaping Post-War Planning Policy

During the Second World War, the CPRE campaigned to protect the rural environment from post-war industrialisation.

The CPRE wanted to influence the Committee on Land Utilisation in Rural Areas, which was a parliamentary committee set up to make recommendations for a new planning act. This act would put into law what rural land could be used for. The CPRE influenced the act by submitting evidence to the committee, in an attempt to prevent the widespread industrialisation of the countryside.

Rural Planning Policy

The Committee on Land Utilisation in Rural Areas was set up in 1941 as a parliamentary committee. Its task was to decide how best to use rural land because previous planning acts had focused on towns and cities. The government wanted a new planning act to provide a planning framework for the countryside. The committee’s recommendations would be laid out in a report that would be key in developing the act.

In autumn of the same year, the Sheffield & Peak District branch of the CPRE submitted evidence to this committee to try and influence its recommendations. The CPRE argued that the Peak District’s scenery was under threat, most notably by the rapid increase of lime and cement works in the region.

The charity saw this as a crucial time for the future of the Peak District, as the recommendations of the committee, designed to be implemented after the war, could shape planning regulations for decades to come. The CPRE presented its own recommendations for how rural areas should be protected by the planning system and asked its members to lobby the committee by writing letters. Evidence was requested in October 1941, but letter-writing by the Peak District branch of the CPRE’s founder and secretary Ethel Haythornthwaite continued well into 1942 until the committee’s Scott Report was published in August. The final contents of the report were remarkably similar to the CPRE’s recommendations.

The Campaign Against Industry

The CPRE told the committee that, “the introduction of industrial concerns of any size in the Peak would be injurious to sound rural life as well as a mortal blow to scenery.” In no uncertain terms, the CPRE were – apart from industries associated with agriculture and tourism – against industrialisation in rural areas.

The Scott Report, named after the committee’s chairman, Lord Justice Scott, seemed to largely agree with the CPRE’s assessment. One recommendation suggested to keep new industry to vacant or derelict sites in towns, and that “where industries are brought into country areas they should be located in existing or new small towns and not in villages or the open country.”

Planning for the Future

By influencing the report, the CPRE hoped to shape the future of planning policy for rural areas. The Scott Report would contain recommendations to be implemented by the government. If the report was in line with the aims of the CPRE, then any planning acts that followed would be more likely to enshrine protections for the countryside in law. At the time, this was not the case. The previous Town and Country Planning Act of 1932 focused on urban areas and offered no protection to much rural land.

Because of this, the CPRE believed that it was an important time for the future of the Peak District and other rural areas, and that a change in planning policy was necessary to halt the rapid growth of lime and cement works and other industries. While there was a relative lack of development because of the war, there was a worry that industrial rural development could expand dramatically post-war due to a lack of protection.

Earles Works at Hope. Taken by EBG (Ethel Haythornthwaite). Copyright CPRE PDSY. Ref: CPRE/A324/603

Local Influence on a National Scale

This concern appears in the letters of Ethel Haythornthwaite, founder of the Peak District and South Yorkshire branch of the CPRE. Correspondence between Ethel and the General Secretary of the CPRE, H. G. Griffin, in late 1941 showed how much the CPRE valued Ethel’s input, requesting her expertise of the Peak local area: “I am especially anxious to have a memorandum from the Peak District,” wrote the General Secretary. Ethel contributed significantly to the charity’s evidence to the committee.

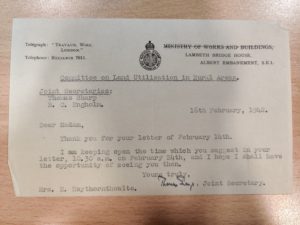

She provided her own local expertise and persistent determination. Even after the evidence had been submitted, Ethel continued to write letters to the committee’s secretaries, highlighting the need for National Parks and other countryside developments; problems faced pre-war that were likely to return and the opposition of large-scale industries in the Peak District. In February 1942, Ethel was invited to meet with the secretaries of the Committee in London, contributing further evidence from the Peak District area.

The Minority Report for Industry

Not everyone was as convinced by the CPRE’s efforts. The minority report which accompanied the Scott Report maintained that industry could be of benefit to rural communities, bringing employment, higher wages and technological advancements to the area. It was noted by both the Manchester Guardian and the Times that these observations were little considered in the Scott Report, which seemed to agree with the CPRE and Ethel.

Town and Country Planning

But the minority report was not enough to influence the government, and in 1943 the Town and Country Planning Interim Development Act was introduced. The Act, drawing on the recommendations of the previous year’s Scott Report, was a success for the CPRE.

Reflecting on these changes in the mid-1950s, Gerald Haythornthwaite stated in his Notes on ‘Outrage’ that the Town and Country Planning Interim Development Act of 1943, “extended the application of planning powers to all land throughout the country.”

Planning had been essentially local, with no planning regulations to guide local authorities in rural areas. A local letter in High Peak News in July 1943 suggested that until that time, countryside protection had often not been a priority for many District Councils, with the CPRE directly campaigning on certain local issues. Discussing Bakewell Rural District Council’s decision not to build new houses in the area, local resident John Barnes said: “I for one am devoutly thankful that our interests in this matter are being so keenly watched by our local branch of the CPRE.” With the implementation of the Town and Country Planning Interim Development Act, planning powers shaped in part by the CPRE would ensure at least some protections for every rural area.

A 1978 article by Andrew W. Gilg calling for a new ‘Scott’ inquiry shows the impact of the campaign. Andrew notes the success of the Scott Report, as many of its major policy recommendations have been accepted and implemented in the post-War period in four of the report’s five key recommendations: the lack of industry and commerce in countryside; the poor state of agriculture; the poor state of village social life; need to preserve local amenities recognised. He did however lament the lack of overall planning direction.

Planning Today

There have been many attempts to shape an overall planning direction since, including most recently the Government’s National Planning Policy Framework, which were met with widespread criticism. The Peak District and South Yorkshire branch of the CPRE believe that these proposals will place all of our countryside – including the Peak District National Park – under increasing threat. The CPRE Peak District and South Yorkshire believe that this framework “places the countryside under increasing threat and leaves local communities and planning authorities largely powerless in the face of developer pressure.”

Following successful campaigning from many groups including the CPRE, the government has U-turned on its decision to implement these reforms, which would have made the planning process less democratic. In many letters and speeches throughout the 20th century, Gerald Haythornthwaite declared that participation in planning and opportunity for public discussion should be encouraged. Echoing Gerald’s words, ministers have promised any new reforms will have “effective local engagement at its heart.” To ensure this is the case, we need to keep pressure on the government. Perhaps the Scott Report can set an example for how that can happen.

References

- Dudley Stamp, The Scott Report. The Geographical Journal. Vol. 101, No. 1 (Jan., 1943), pp. 16-20 (5 pages)