Stories from the Archive 3: Long and Winding Roads

The CPRE has campaigned about transport in the national park since the 1950s, and it has taken on a new urgency due to the climate emergency.

Roads and the Peak District

UK Road traffic started to increase dramatically in the 1950s. This led to a programme of road building and widening, roundabouts, bypasses and major new road schemes. The CPRE responded with a campaign to reduce the impact of road building on the beauty of the Peak District National Park. Their campaign techniques included letter writing, lobbying government ministers, raising public awareness, attending public enquiries, conducting traffic surveys, being part of transport committees and commenting on specific proposals. Perhaps the greatest success was to prevent the motorway being built across the northern part of the National Park. This is a campaign that continues today and remains a priority.

Why was it about roads?

Five times more people owned cars and more lorries carried freight between 1950 and 1970. By 1970, 77% of all passenger miles were by car and 80% of freight was carried on the roads. The numbers of cars on the roads doubled again between 1970 and 2000.

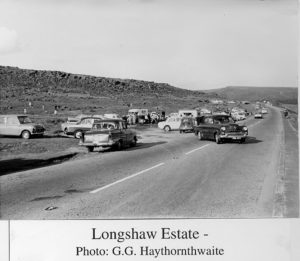

Government and councils responded to more vehicles by building more roads. They began the motorway system with the M1 in 1959. Main and minor roads were improved and widened, the modern roundabout was invented, and towns were bypassed. People benefitted from better roads and car ownership with greater mobility and access to the countryside. More and more people visited the Peak District by car.

Small changes driven through

The CPRE welcomed the increase in visitors, because they wanted people to enjoy the Peak District’s peace and beauty. The issue was how new roads damaged the countryside and increased noise pollution. The county highways agency widened roads, built concrete bridges and installed large roundabouts, all without needing planning permission. The CPRE wanted to limit this road building in the National Park.

Gerald Haythornthwaite created a motor vehicle memorandum in 1963 when he was Chair of the CPRE’s Standing Committee for National Parks. The CPRE always offered practical solutions and lobbied for the improvement of passenger and freight rail services and campaigned against the closure of two threatened TransPeak railway lines in the 1960s – Hope Valley and Woodhead lines. The Hope Valley Line is open to this day, but the Woodhead line closed in the 1980s. Gerald saw the Woodhead Line as the answer to transporting Buxton limestone to a steel plant that opened in Scunthorpe in 1971. He created a plan to replace mineral lorries with freight trains departing from the railhead at Buxton.

Campaign Tactics

The CPRE wrote letters to government Ministers, the county highways officer and to newspapers. They also surveyed traffic patterns, objected to proposals and commented on public consultations.

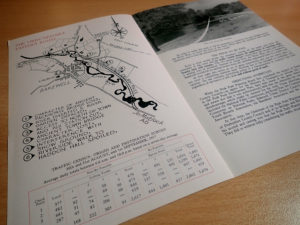

Gerald Haythornthwaite was in the thick of the action and wrote an article for the Institution of Highway Engineers in 1970. He argued for the development of a road system in the Peak District that would do least harm to the countryside and benefits road users would be met by a closer involvement of the highway authorities in the wider issues of planning. He covered road patterns, terrain, traffic types, future trends, deflecting traffic, motorways, A roads, minor roads, car parks and motor-less zones.

Peak Transport Policy

The CPRE persuaded the National Park Authority to study transport and road improvements across the Peak District in 1979. The report recommended keeping the Woodhead Railway open for freight, assessing whether the Snake Pass should be closed to through traffic, advising the Highways Authority that minor road schemes would not alleviate traffic problems and that traffic issues in the Park should be a multi-agency issue.

The CPRE commented on the report to ensure that their views were heard. They focused on three issues they were most concerned about:

- The Woodhead Line.

- Introduce a 3-ton weight restriction on the Snake Pass.

- Object to a Bakewell relief road to take traffic around the village.

Two notable transport campaign successes for the CPRE centred on Bakewell and Longdendale.

Bakewell Bypass

The plan to bypass Bakewell’s town centre began in 1936 and resurfaced in 1957.

Proposal and Campaign

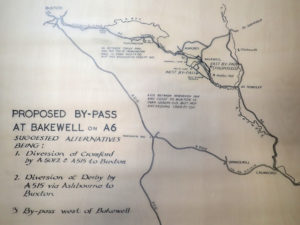

The County Highways wanted to divert the A6 by building a wide, fast road across the water meadows by Holme Lane and the Show Ground to the northeast of the town. They propsoed a new junction with the A619 at its junction with Coombs Road and a long, modern bridge.

In 1936, Gerald wrote an article in Derbyshire Countryside magazine and had 500 copies printed as a leaflet. He described Bakewell as the kinder side of Derbyshire’s nature and stated its outstanding charm was the town’s relationship with its river pastures. These would be lost, as would the visitors who were attracted to the town’s peace and beauty. The CPRE estimated that the bypass would be of no benefit to motorists, who would only gain three minutes journey time, while the intrinsic life and charm of Bakewell would be lost. The scheme was dropped in 1937.

The Road Returns

When the bypass was proposed again in the 1950s, the branch campaigned against the disfigurement of Bakewell once again. The branch proposed alternatives to the scheme. A public enquiry was held in 1969. Despite the presentation of the CPRE’s convincing objections by Gerald and an attorney, the National Park Authority and the government approved the scheme. It has never been implemented and would, surely, now be seen as an act of landscape vandalism.

The Longdendale Motorway

The proposal for a main road or motorway between Manchester and Sheffield was announced in 1972 in the House of Commons. It would be built through Longdendale.

The CPRE Responds

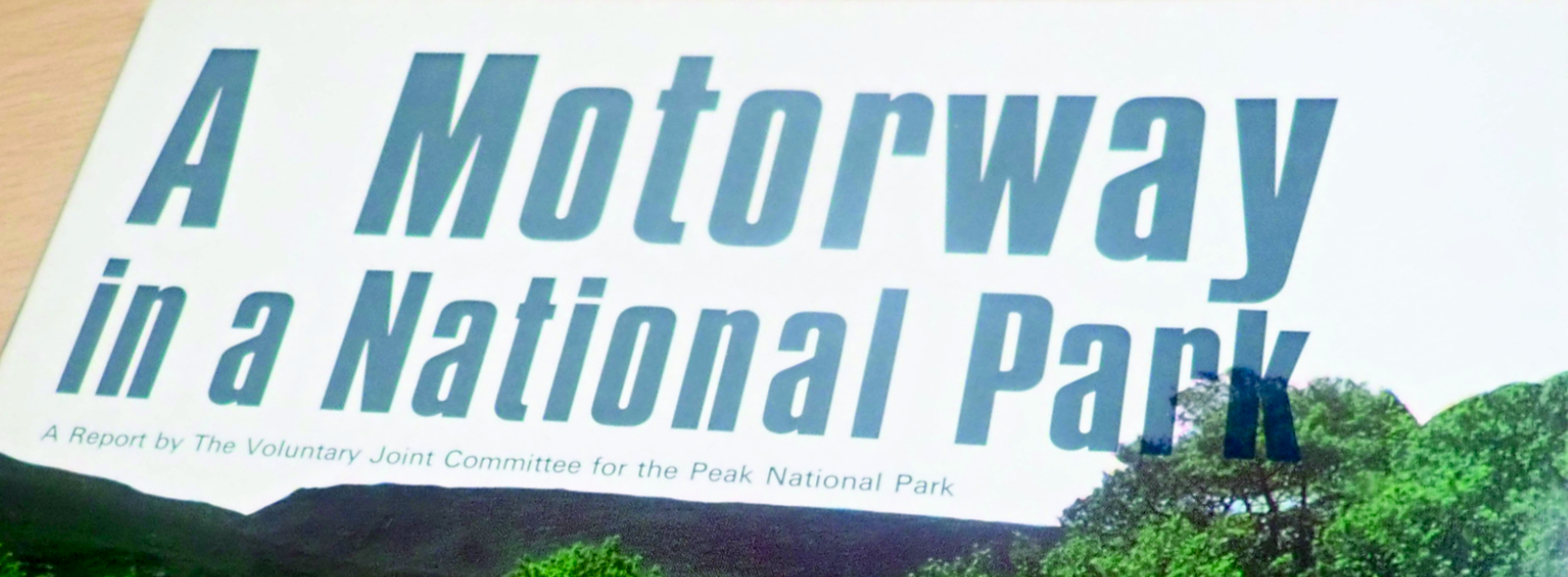

The CPRE quickly co-ordinated a group of organisations called The Voluntary Joint Committee for the Peak National Park. The aim was to raise public opposition to the plans before the proposals went to public consultations.

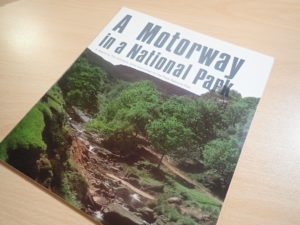

They produced a booklet with photos of the M62, plans of the predicted route, a photo showing an M62 viaduct overlain in Longdendale and evocative language. They visualised a motorway similar to the M62 – a wide road, with concrete viaducts, deep cuttings, the ‘alien presence’ of sodium road lights ‘projected into the night and the glare of the lights radiates far over the country’, traffic interchanges and a maintenance slip road.

‘The dominating structure of a motorway having no response to the nature of the land, disregarding its natural formation and deforming its features would diminish its natural beauty. The din, stink and feverish movement of the motorway traffic would drive out peace. A motorway therefore is wholly incompatible with the two purposes of for which National Parks have been established.’

The booklet proposed alternatives to the motorway, to develop the Woodhead and Hope Valley railway lines. They went into technical detail of the capacity, cost-effectiveness and low-carbon benefits of the Woodhead’s electrified line. This included feeding energy back to the electricity grid via regenerative breaking downhill. The booklet ended with an appeal for donations and urging members of societies to pass a resolution to object.

The Roads Lobby

The scheme’s backers promoted the benefits to Sheffield’s economy, attracting new industries, reducing freight costs, and improving journey times. There were also benefits seen to taking traffic away from small towns and villages nearby and off the Snake Pass and Hope Valley Rd.

Gerald also gave talks and wrote letters to newspapers, often in response to supporters of the motorway.

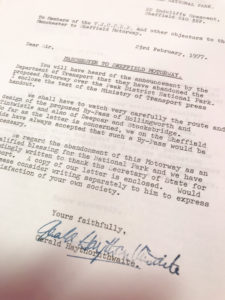

The Ministry of Transport continued with a traffic survey of the route until 1977 when the proposal was scrapped ‘until 2000.’ The scheme was replaced with plans to improve the existing A628, including bypasses at Tintwistle, Hollingworth and Mottram. The scheme has returned as a dual-carriageway expressway.

Today

‘We have for many years campaigned for solutions that address the problems.’

Download the CPRE’s transport policy, and read about campaigns and practical solutions for sustainable transport. You can complete an online survey and see what actions you can do in response to the TransPennine expressway. The CPRE continues to support improvements on the Hope Valley Line so that it remains an alternative to the car.