Stories from the Archive 2: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

What do you consider to be the main threat to the countryside today? Perhaps climate change or planning issues, road-building or litter? If you had asked the same question a century ago, the answer would have been one word: ugliness.

In 1924 a small group of people, led by Ethel Gallimore [later Haythornthwaite], founded the Sheffield Association for the Protection of Local Scenery, the forerunner of today’s Peak District and South Yorkshire branch of the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England [CPRE]. The group was alarmed by the increasing threat to the beauty of the Peak District on their doorstep. They began raising awareness through lectures and exhibitions, letters and publications. The ‘beautiful and the ugly’ was a theme that appeared regularly over the coming decades.

The Threat of Ugliness

The timing of their campaign to save the countryside from ‘ugliness’ was not a co-incidence. The 1920s was a period of rapid change. More people owned cars and enjoyed trips to the countryside; some were keen to relocate permanently. There was pressure to widen roads and replace bridges and ‘ugly and ill-placed’ petroleum filling stations appeared. Advertisement hoardings sprang up, littering increased and refuse tips were a problem. Amenities such as electricity and telephones, requiring pylons and poles, spread to rural areas. Modern industries based in the countryside, such as quarrying, expanded.

But the chief cause of ‘rural disfigurement’ for the campaigners was uncontrolled building development. This was “often entirely out of harmony with the character of its natural surroundings” according to the Association’s 1931 Annual Report. With no effective planning legislation, no National Park and no Green Belt, there was little in place to stop ugly and out of place building.

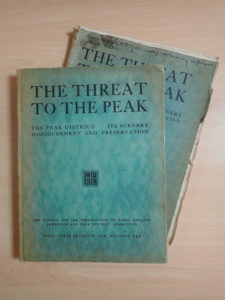

The Threat to the Peak

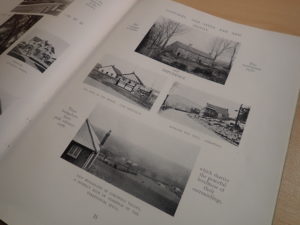

In 1931 ‘The Threat to the Peak’ was published by the Sheffield and Peak District Committee of the CPRE. This beautifully illustrated book included short chapters on each of the main ‘threats’. The author of the chapter on buildings did not hold back: “Hundreds of vulgar villas, complete with fussy facades, creep up the hills out of Sheffield, and odd specimens of the same type shatter the harmony of remote villages. Pink bungalows suddenly appear in the heart of a wooded dale or austere moor, ruining acres of noble scenery”, they wrote.

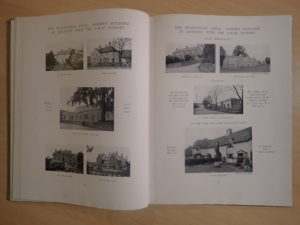

The author went on to explain the impact that inappropriate building had on the landscape before highlighting the need for public ‘enlightenment’ and the responsibility of local authorities. Photographs showed traditional buildings alongside ‘suitable’ and ‘unsuitable’ modern buildings.

Including ‘suitable’ modern buildings was important. The Committee was not simply ‘anti’ everything modern. It accepted that new affordable houses had to be built and that many of these would have to be in rural settings.

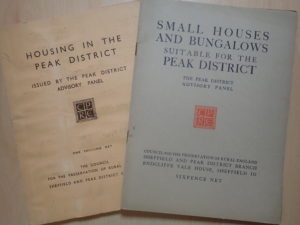

Housing in the Peak District

More detailed advice arrived in 1934 with the publication of ‘Housing in the Peak District’ – the forerunner of the modern ‘Design Guide’. The authors explained that old buildings in rural areas were constructed of materials found in the neighbourhood – in the Peak District this meant stone – and had a distinct local style. Buildings were also designed to fit their location – “they seem to grow naturally out of their surroundings and to increase their beauty.” Modern buildings often ignored these factors in their choice of materials (including colour), design and location.

The main aim of Housing in the Peak District was not to criticise, but to suggest designs which would harmonise with the old buildings and the landscape. Local stone was too expensive to be used as a regular building material, so the authors recommended inexpensive alternatives. These were listed in an appendix, complete with suggested suppliers and a price list. Suitable building materials were available for viewing at the Committee’s headquarters.

Small Houses and Bungalows for the Peak District

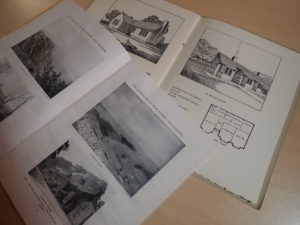

Further practical help from the Committee came with the compilation of a portfolio of drawings of inexpensive houses and bungalows. These were presented in an easily accessible form in Small Houses and Bungalows suitable for the Peak District published in 1936. The illustrations consist of an ‘artist’s impression’ of the houses, floor plans, materials, and approximate building costs.

Legal Protection

Alongside this work, the Committee had campaigned hard for the establishment of the Sheffield Green Belt and the Peak District National Park. The Town and Country Planning Act was passed in 1947. But despite these successes, the pressures on the countryside continued.

The Case for Preservation

The campaigners felt it was necessary to keep making the intellectual case for preserving ‘natural beauty’. In 1966, forty years after his wife had founded the Sheffield Association, Gerald Haythornthwaite gave a talk on the BBC Home Service. His subject was ‘My Case for Preservation’ and he began by stating: “The most noticeable characteristic of the 19th and 20th centuries, and especially the 20th, is ugliness.”

Gerald was concerned about irreparable damage to the countryside from industrial activity and the loss of regional diversity in the rural landscape. He argued that people needed to connect with nature, not just for ‘delight and inspiration’ but also for their mental wellbeing – a strikingly modern idea. A BBC producer wrote afterwards that the talk was “one of the most successful we have broadcast for some time”.

Letters of appreciation from listeners and other articles by Gerald on the theme of ‘rural beauty’ and its survival are now preserved in the archives of the Peak District and South Yorkshire branch of the CPRE housed in Sheffield City Archives.

Beauty Today

Many of the issues familiar to the pioneer campaigners are still with us today. The work of the Peak District and South Yorkshire branch of the CPRE includes planning and transport issues, quarrying, overhead powerlines and litter and fly-tipping, alongside challenges such as the climate emergency. The branch has many practical ideas for what you can do. It also continues to advocate for high standards in landscape and building design.

And while ugliness is perhaps not a word we use today when speaking about the threat to the countryside, the campaign to preserve natural beauty which Ethel and Gerald Haythornthwaite and their fellow campaigners started is very much ongoing. The aim of the CPRE remains to promote the beauty, tranquillity and diversity of the countryside in the Peak District and South Yorkshire for everyone to enjoy now and in the future.